Note: in the following piece, I’ve chosen to capitalize Maple as a proper noun when I refer to the living tree or what the living tree makes for its own life pattern: Maple tree, Maple roots, Maple sap, Maple sapling . . . When referring to the benefits, processes and products that are part of the human relationship to the Maples, I use the lower case “m”: maple syrup, maple sugar . . .

Maples Through the Year

Each year, I notice the Maple flower buds when they open because we have two big, old Silver Maples in our front yard, and I love the way their rosy red blossoms look in the early morning light. They used to predictably swell and burst in mid to late March, but this year they began to open in the second week of February.

I’m grateful to share a world with generous Maple trees. Abundance is their way as their samaras (winged fruit with seeds) rain down and their woody interior vessels flow with so much more sugar rich sap than they need for their own growth and sustenance. The sweet, brown taste of real maple sugar or syrup that is made from the sap of Maple trees is truly one of my favorite flavors.

Our weirding climate has become increasingly warmer and unpredictable. This warming trend was intensified this winter by a stronger than usual El Niño affect. From December through March our weather was very mild and hardly felt like a winter at all. We had very little snow and, other than a few isolated weeks of cold, the temperature was most often above freezing. I’m concerned about how the Maples will be affected by our rapidly changing weather patterns. Northern species of Maple trees, like Sugar Maple and Red Maple, thrive in a climate with four distinct seasons that include a frozen winter followed by a slowly warming spring thaw.

The full, leafy crowns of Maples offer welcome shade in the heat of summer for a variety of creatures, including humans. Maples are foundational species in their ecosystems providing opportunities for shelter and nesting locations for many birds, mammals and insects. They are a dependable food source for wildlife with their abundant samaras wheeling through the air in late summer, whispering as they fall to the ground.

In mid-autumn, Maples become a brilliant blaze of visual fire in the northern woods as their leaves change from multiple shades of green, to golden yellow, saffron orange, and vermillion red in response to hard frosts that come at night and the warm sunny days that typically have characterized our late October weather. This color palette of the Maples, combined with the bright yellows of Birch leaves and the deep wine and brown of Oak leaves, draws tourists from hundreds of miles away to the woods of northern Michigan just to walk among the trees and take in their seasonal beauty.

Deciduous trees, like Maples, that lose their leaves before winter, look beautiful with a fresh layer of white snow adorning their gray-brown branches. Prolonged frost conditions help to control insect pests and other pathogens that might challenge the trees. A good snow cover is important to the health of all trees that live in the north. Consistent snowpack helps to insulate tree roots during brutal cold snaps when the temperature dips below 0°F for a string of days. If we have frigid weather like that without an insulating snow layer on the ground, roots are at risk for damage. As conditions warm a little, melting snow pack also waters the roots well at the beginning of the growing season. This soil moisture from the snow pack is significant to the health of Maple roots. Without it, they wither and die back before the spring rains fall.

When the spring thaw happens after a snowy winter, sugar rich sap rises up from the roots and fills every vessel in the sapwood, up through the highest branches of the Maple tree. Then as the temperature plummets with the sunset, the sap freezes there, up in the limbs and crown and throughout the trunk. It stays, frozen, within the tree and branches during the long cold night. On the next warm, sunny day, it melts and flows downward so that if a small hole is drilled in the side of the trunk, through the bark and cambium layer and into the sapwood, that sap will trickle out and into a waiting bucket. The sap can be boiled down to make maple syrup. Boiled even further, and it crystalizes to make maple sugar. It takes approximately 40 gallons of sap to make 1 gallon of maple syrup. This equation reminds me how precious that sweetness is.

Historically, the season’s Maple sugaring ends, and spring has fully arrived, when the ground has thawed and the Maple tree’s flower and leaf buds swell and begin to burst. When that happens, the sap yellows with different nutrients needed for the tree’s growth and it becomes sour tasting. It’s time for the Maple tree to settle into growing a new crown of leaves and more branches and begin to make more sugar in the sun and warmth.

Humans and Maples

Collecting Maple sap is an ancient human tradition on this land in the lower northeastern area of this continent, known to Indigenous people as Turtle Island. For many hundreds of years, Anishinaabe and Haudenosaunee peoples have been gathering in early spring to collect Maple sap and boil it down into sweet syrup and blocks of maple sugar that were easily carried and preserved. The mineral rich, light brown sugar can be used for all kinds of culinary purposes including preservation of meat, to sweeten other foods, as a sweet treat for quick carbohydrates, and historically it was also valuable for trading with others. Today, it continues to be a source of income for northern Indigenous communities.

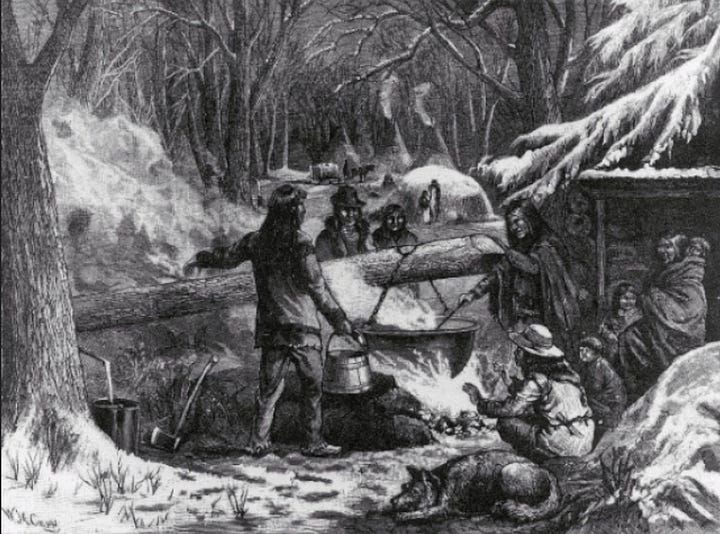

The process of tapping trees was traditionally done by cutting a small “v” into the side of the tree trunk that was deep enough to go into the living sapwood. A small carved wooden spile was inserted into the cut area to divert some of the sap via gravity into a waiting birch bark basket or wood trough. Historically, both for the original Indigenous inhabitants, and for the European settlers who learned the process from them, maple sugaring was a communal event that involved people of all ages. It was a convivial time to gather and greet each other again after a few months of hunkering down in smaller family groups to get through a cold winter. Collecting sap-full containers, and evaporating the sap over open fires until it turned to sweet amber syrup took a lot of time and engaged many hands to get the work done. During the process there was often merrymaking with song and storytelling, sharing from what still remained in the winter larder, and of course the enjoyment of an abundance of sweet syrup and sugar that resulted from good labor.

Long ago, trading the sugar and syrup made from the Maples for other goods and services was common practice. Eventually, in an increasingly profit motivated modern economy, maple syrup became a way to make money for tribes and for settler families. Today, maple syrup is referred to as an “industry” with an economy that globally amounted to the equivalent of $1.5 billion US dollars in 2021. In order to amass enough maple syrup for that kind economic payout, “producers” have to employ methods like vacuum extraction with a vast system of tube lines that can be tapped into thousands of trees at once, increasing the sap “yield” by 50 to 200% in a season.

In 2010, during a research project that was investigating sap flow at the University of Vermont’s Proctor Maple Research Center, a couple of scientists made a discovery that they felt could further improve the yield of Maple sap and perhaps offer an answer to climate related problems and damage from invasive pests like the Asian long-horned beetle. The process involved cutting the entire crown of branches off of 4” Maple saplings and attaching a vacuum extractor cap to the small trunk. The surprise at their results can be heard in this quote that includes the words of one of the lead researchers, Tim Perkins:

“We got to the point where we should have exhausted any water that was in the tree, but the moisture didn’t drop,” says Perkins. “The only explanation was that we were pulling water out of the ground, right up through and out the stem.” In other words, the cut tree works like a sugar-filled straw stuck in the ground. To get the maple sugar stored in the trunk, just apply suction.

This technique is in the development stage, awaiting effective cap technology to fit onto the top of decapitated saplings. In the meantime, research continues into ways to grow dense Maple sapling plantations for maximum sap yield. The research team is optimistic that this technique will eventually be a way to intensively extract more Maple sap on less land, thereby increase syrup production even with the growing challenges of climate change.

After I read about this method of vacuum extraction through beheaded Maple saplings as a strategy for increasing maple syrup production, I sat quietly for a bit, picturing this process and feeling a deep sense of dread.

The researchers suggest that any images of a continuance of a human heritage of relational Maple tapping is romantic, but impractical for the future. The future they claim is another extension of the mindset that only values the use of living beings as things to be extracted from with little compunction for the soil or the lives that are simply used up and cast aside. There is no care for relationship, only the financial bottom line and the false abundance of product.

In my head, juxtaposed pairs of words assembled:

harvest / yield

community / industry

sugaring / extraction

trade / profit

tapping / vacuum extraction

Maple sap / product

life-way / business

forest / plantation

relationship / transaction

These word pairs hold much for us to consider.

And now, I’ll share a story . . .

Winter 2024: One Family’s Sweet Maple Story

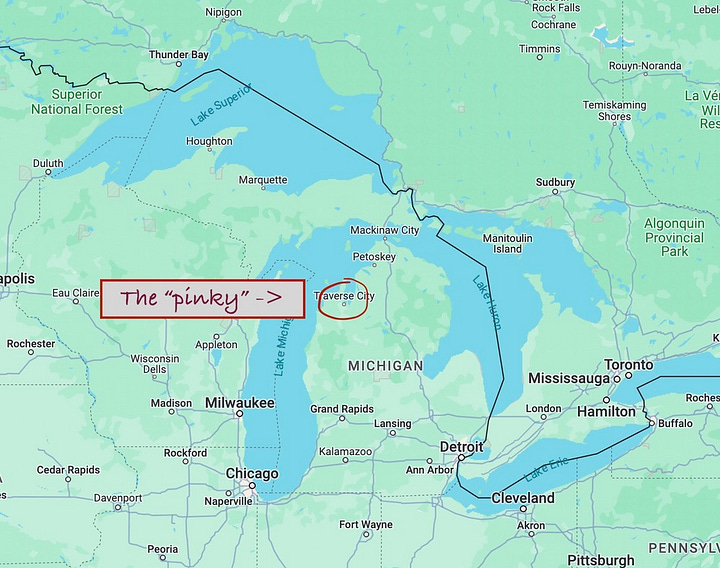

Our niece, Joelle, lives a few hours northwest of us near the “pinky” of Michigan’s mitten (see the map below). She and her husband Jack, and their son Alwin, and sometimes Joelle’s mom, Teresa, have been tapping Sugar Maple trees on their land of a few, mostly woody acres for the last 5 or so years, since Alwin was a toddler. We’ve been lucky to be gifted a bit of that sweet amber gold a few times over the years since they’ve been doing it.

I talked with Joelle early in March and asked her if they had tapped the maples again this year. She paused for a moment before she answered my question, and I could hear a quiet disappointment in her voice as she told me they didn’t end up doing it. She explained that it had been a challenge to choose a good time to tap their trees with so many temperature fluctuations and long warm spells throughout January and February. In order to draw enough sap to make syrup there has to be at least a solid week of nights that are consistently below freezing, and days that are sunny and above freezing. All frozen or all warm will not produce a good sap run.

In the midst of indecision about when they might do it, they heard that because of the warm, El Niño winter, coupled with the chaotic fluctuations of climate chaos, the Anishinaabe bands in northern Michigan would be letting the trees rest this year by not tapping them. They have a traditional ethic of care and forbearance in their long relationship with the Maple trees that wisely suggests that tappers give trees a year of rest after 4 years of tapping.

Joelle and her family were thoughtfully reflecting on this news, and heading toward the wistful decision to possibly let it go for this year, when a friend of theirs offered them all of the sap he had left after making enough syrup for his own household. He had only tapped three of his trees in February and gotten way more than enough. Even though it felt a little complicated after all that thoughtful ruminating about what to do, receiving that sap and processing it was a lot better than having it go to waste—and they would still be able to engage in part of their family tradition.

They spent many hours together boiling the sap down over an open fire, singing songs and tending the flames. In addition to not tapping the trees this year, Joelle said she also missed one of her favorite parts of the process, drinking cold, fresh sap, straight from the tree. Jack missed hearing the music of the sap drops plinking into the buckets strapped to Maple trunks. But Alwin still enjoyed his favorite part of the process: gathering scruffy Jack Pine limbs and feeding the fire, and he was very happy to carry on at least part of their maple sugaring tradition that he had come to love. They all appreciated a day together by a fire that held the promise of sweet, amber, maple syrup to enjoy for months and months to come. They ended their sap boiling time tired and permeated with the familiar smell of smoke, but grateful.

Joelle told me that a few years ago they began their own homemade tradition of Wassailing the Maple trees by singing to them and pouring out libations over the roots. You might be familiar with the practice of Wassailing homes on 12th night (January 5) by going door to door, making a joyful noise with song, and drinking to the health of the home with the people who live there. This is an ancient Anglo-Saxon practice that has been carried on, and it’s also traditionally done to bless the apple trees with song and poems, and drink to their health in winter so they might have a fruitful harvest after the year’s growing season. This past January the Maples had been properly Wassailed by Joelle’s family, a time that normally would be well ahead of preparation for another tapping in March.

Though they didn’t tap their own beloved trees, they did take a walk together one day to visit them. On this March walk, instead of bringing their drill, spiles and buckets, Joelle and Jack and Alwin searched the bark of their trunks to find the old, healed tapping scars from previous years. The family reflected on those times and hoped to be able to receive that good sap again. They touched the scars with care and remembrance. They talked about how this year some people had tapped as early as January, and wondered if in the coming years they might need to wassail the Maples much earlier than January 5th, so that their gifts and blessings for the trees will be offered well ahead of the time when they might be tapped—if the conditions are right.

In the meantime, instead of giving up a portion of their sap this year to the human creatures who made offerings and sang to them, the Maple trees that share the land with this family will have an abundant period of rest, with much more than enough sap in their own bodies. They’ll continue to feed the mycorrhizae that are entangled with their roots, who will share that sugar with other roots, and tiny organisms that are members of the forest soil ecosystem. An economy of generosity.

The Generosity of Limit

To care for what we know requires

care for what we don’t, the world’s lives

dark in the soil, dark in the darkForbearance is the first care we give

to what we do not know. We live

by lives we don’t intend, lives

that exceed our thoughts and needs, outlast

our designs, staying by passing through,

surviving again and again the risky passages

from ice to warmth, dark to light.Rightness of scale is our second care:

the willingness to think and work

within the limits of our competence

to do no permanent wrong to anything

of permanent worth to the earth’s life,

known or unknown, now or ever, never

destroying by knowledge, unknowingly,

what we do not know, so that the world

in its mystery, the known unknown world,

will live and thrive while we live.

~Wendell Berry

“A Small Porch in the Woods, Section 9”1

In the poem excerpt above, the farmer, poet and sage, Wendell Berry, asserts: Forbearance is the first care we give to what we do not know. To forbear is to hold the challenge that presents, and to respond with a generous measure of thoughtful restraint. To pause and examine all the strands you can discern in the knotwork and then be willing to give up something for the greater whole if need be.

If we can agree that Maple trees are not robotic factory components maintained solely by humans, and if we also acknowledge that they are living, breathing creatures that grow along side of us in a diverse community of creatures, we might also agree that our human relationship with the Sugar Maples can expand beyond the cash or pleasure we receive from their sap. How do we reciprocate the sweetness we have received from these trees, in kind?

The traditional Anishinaabeg wisdom to offer a fifth year of rest to the Maples after 4 years of extraction as a kind of Sabbath, is a practice of forbearance. It allows for some breath in between actions. If taking a year off is an economic hardship for someone who works with the land and depends upon that income, forbearance could look like making the decision to simply gather only what you need to sustain, and not a drop more. It could be rotating the trees that are tapped in five-year cycles, four on and one off, or some other rhythm that provides regular time off for the trees. If you’re a small tapper who partakes only for your family and friends like Joelle’s family, forbearing might look like deliberating about whether to tap at all, and then being gifted with the surprise of sharing in the excess that someone else has tapped, so that it is not wasted—and then savoring that gift each time it is tasted.

We humans are powerful in this world. We are absolutely capable of destroying it and we have destroyed many different kinds of lives with our actions. This is fact. We have a responsibility, as only one creature among many, to hold an awareness of this potential in order to temper it. Perhaps more than any other creature that we share this Earth with, we also possess the ability to decide how we hold and wield our power, how we choose our way of being. This choice is present to us in every relationship that we engage in. To be ignorant of this reality is to comply with the ongoing destruction of our only home and her life providence, the world in its mystery, the known unknown world.

Ideologies and political stances that suggest humans can’t possibly have a significant effect on the forces that drive our climate, miss this point and support further extractive reduction of the true wealth of life. It is not that we can design our climate or control it, humans cannot do that, though many are trying to prove that we can fix our mess with more technological innovations and grand plans. However, our activities do have an effect upon our atmosphere, and atmospheric changes affect our climate.

Trees have an effect on the atmosphere, taking down carbon and putting up oxygen. Termites and cow farts do the opposite—and so do humans, at an ever increasingly alarming rate, with our insatiable appetite for clearing forests and burning things—every minute of every day. This capacity for destruction is what requires the need for us to exercise forbearance.

If we can accept that forbearance is a necessary quality in relationship as an expression of care for the other and for what we do not know—other people, other lives, an essential valuing of life itself—then we may naturally arrive at the “second care” that Berry commends to us: “Rightness of scale.”

Rightness of scale is our second care:

the willingness to think and work

within the limits of our competence

Any way I look at it, the image of a densely packed acreage of thousands of decapitated, Maple seedlings hooked up to the tubes of vacuum extractors, like Franken-trees, with nearly every bit of sugar that was stored in their roots and flowing in their sapwood in the first few years of their lives, being mechanically sucked away along with water and essential minerals in the soil, seems darkly dystopian. It demonstrates an astonishing lack of a rightness of scale. The fact that this method is being devised in part to help save maple farmers from the possibilities of economic hardship caused by anthropogenic climate change feels like deep irony. It also assumes that we know enough to actually do something like that without incurring unintended consequences.

The point of what Berry calls the limits of our competence is a recognition that we don’t actually know all of the possible outcomes of our actions. When we begin to think we can control and safely reduce the behavior and patterns of living systems—like the relationships that exist between whole trees, their life processes, the fungal mycorrhizae, microbial relationships, minerals and other soil components, along with all of the other ways they are entwined with the other creatures in their natural ecosystem—we have strayed from a basic respect of the value of life. Even if we think we know everything we need to know about what we’re doing, there are always unknown variables. Failing to recognize this and to heed limits, has brought us to the great damage we are feeling the effects of now. We act in a condition of ignorance of an important sensibility that reminds us, and invites us, in Berry’s poetic words:

to do no permanent wrong to anything

of permanent worth to the earth’s life,

known or unknown, now or ever, never

destroying by knowledge, unknowingly,

what we do not know, so that the world

in its mystery, the known unknown world,

will live and thrive while we live.

Maple trees are just one kind of life, and like all other kinds of life they are deeply entwined with others. We don’t actually know exactly how our rapidly warming climate will ultimately affect them, or myriad other kinds of lives and their ecologies, but we have a growing number of situations that we do know enough about to be concerned, and there will be more extinctions. If we can admit that we don’t know right now what the impact of Climate Change will be on Maple trees, and if we continue to tap them at the same or at an increased volume than we tapped a generation ago when the weather patterns were consistently familiar, then it seems like a good idea to pause, or at the very least to tap less with greater discernment and to exercise forbearance.

In this finite world, we must begin to live within natural limits and accept that each of us cannot have unlimited access to whatever we desire, even if we can pay for it or devise machinery to make it happen. Maybe something like maple syrup is sustainable only at a small, regional scale and shouldn’t be available to purchase thousands of miles from the nearest stand of Maples, especially when the conditions that enable its abundance are changing. Perhaps it is a substance that is tied to its place and its relationship with the people there.

I’m moved by the generous and mindful relationship between Joelle’s family and the Sugar Maple trees that share their home. They reveal a way that we can choose to be in this world that privileges life, relationship and wellbeing over immediate gratification and a desire for more; a way of forbearance and thoughtful scale. That kind of lively, reciprocal entwinement with the others who your share your home is part of a commitment to live in service to mutual flourishing, not just taking what you want with little regard for the whole.

Joelle shared with me that as they go forward, they will continue to thoughtfully discern their way with the Maples:

“I think we’ll take it as it comes, but continue to look to the tribes and see what they’re doing and use that as kind of an example of good stewardship, and maybe we’ll do fewer taps. In the past we’ve done ten taps and have often had more sap than we could boil. As it is now, every year we don’t do the same trees, but maybe if we’re tapping less, we can also take more years in between tapping. I just hope that nothing happens to the maple trees. I often think about the big tree diseases and pests that come through, and how devastating it would be if something were to take the Maples.”

They may not be able to control all of the threats to the Maples, but Joelle, Jack and Alwin will continue to wassail them, honoring their relationship well ahead of any activity related to harvesting their sap. And they will thoughtfully discern their way forward in their decisions about tapping the trees. Their active engagement with the Maples is not only care for the trees, it is a beautiful, real life learning experience for a growing child to learn about how people can consider their actions in relationship with other kinds of lives, experienced in real time as the adults in his life process and discern and include him in that decision.

Forbearance and considering the rightness of scale are choices we can make to contribute to the thriving of others in our lives. A willingness to put off what we desire for the good of someone else is part of our belonging with one another in a family or friendship, a convivial way of tending to our connections.

Moving forward in this fraught world, this must extend beyond exclusively human relationships and into the more than human world of all life, in which we are deeply entwined, whether we recognize this reality or not. I don’t know exactly what caused some kinds of people in this world to become so separated from this reality and then proceed to act in such destructive, selfish ways. For people like me, who are descended from European settlers on this land, respectfully looking to our Indigenous community members who are recovering their lifeways after centuries of genocide and displacement for clues about how to recover our own relationships with this beautiful earth, seems very appropriate.

There are no truly separate lives. There is only interconnected life and ignorance of that can lead to the peril of all. To treat other lives as mere things to extract from with no recognition of their living entwinement enables us to destroy or harness them as components that exist only to fill our desires.

To move beyond the separation that delineates a narrow definition of “people” from others that are “things,” will take a lot of reframing of thought and a recognition that we literally cannot know all of the consequences of our choices. Awakening to this unknowing and the reality of our essential entanglements with other lives is a kind of humbling and gentling that humans need in order to live well in our own lives in community with other lives.

We can learn and choose to exercise our uniquely human capacity to make choices that consciously support the flourishing of life, among the lives we know, with caution and care for the possibilities we may not know.

To care for what we know requires

care for what we don’t, the world’s lives

dark in the soil, dark in the dark

Wendell Berry. “Sabbaths 2014, VIII: A Small Porch in the Woods” in A Small Porch: Sabbath Poems 2014 and 2015, Together with The Presence of Nature in the Natural World: A Long Conversation. Berkely, CA: Counterpoint (2016), p. 24.

Read: Maple syrup season came weeks early in the Midwest. Producers are doing their best to adapt. by Melina Walling, March 8, 2024, AP. Recent news on 2024’s sugaring concerns.

Go to: Sen’s Anarchist Audio Library to listen to a reading of "Braiding Sweetgrass" Chapter 7: Maple Sugar Moon - Robin Wall Kimmerer” and then, if you don’t have the book, buy it. It is wonderful and important.

Check Out: Joelle’s Zine: Merry Old Soul, “an anti-facsist zine of seasonal culture for all people.”