Dearest Fellow Earthlings,

I hope you’re finding fertile ground for the good things you want to tend, especially in this long season of growing concerns, outrageous distractions and needs for your attention and action. It’s always a good time to take a look around and be aware of blessings, but just now it may feel a little harder than usual. Hold your beloveds close and send love out there. Righteous, protective rage is a form of love. Showing up is care.

A little more than a year ago, I shared a piece here about the grounding practice of foraging wild foods. As we live in the midst of rampant and chaotic greed, hateful disconnect and unearthing, the practice of gathering wild nourishment is one small thing that can help ground us within our humanity.

The following piece about our relationship with Stinging Nettle, is the first in an occasional series that will focus on some of the common, seasonal edible plants that are likely to be near to you. Many of these wild plants are considered to be unwanted weeds. In the modern endeavor to control what grows around us, we have rejected and forgotten our rich relationship with what is provided by nature. Forager and writer Samuel Thayer reminds us, that nature’s garden brims, “Food is everywhere, in all directions.”1

Here, I want to offer more than simply how to find and use a wild plant. In my house, we eat the Nettles we harvest from our yard and elsewhere, in a variety of ways: soup, tea, pesto and pretty much any way a cook might use steamed or sauteed greens. A primary relationship with any foraged food is the gift of nutrition and flavor that humans can receive. Here, I want to expand the relationship beyond simple use and include more than the immediate human benefits.

This essay is meant to invite you to come to know and appreciate a plant that is often misunderstood and treated more like an enemy invader than a neighbor.

Befriend the land. Grow roots. Eat your weeds. Soften your heart. 💚

Stinging Nettle: Awakener, Nourisher, Healer

Once you have developed a good-natured relationship with Nettle, you will shine. Nettle will bring their twinkling light into your eyes, bring your hair and skin to a polished glow. Nettle will help modulate the conversations in your body, and lead you towards a bright and sparkly focus.

~Dirt Gems: Plant Oracle Deck and Guidebook, #63 “Nettle”

First Sting

On a warm April day, during our first spring in our house (35 years ago!), my husband Michael and I were working in the garden plot in the back yard, making it ready to plant the summer garden we had dreamed of all winter. As I was pulling weeds, my bare arm brushed against a small seedling that felt a little prickly . . . and then the prickle turned into a buzzing wave of discomfort that raged across my skin. It felt like a swarm of microscopic bees stinging me at the cellular level, and a hot prickly feeling seemed to grow stronger with each minute. Rubbing it gave no relief, but running it under water helped.

After a while the worst of the pain faded, and then a mild discomfort and strange feeling of sensitivity lingered for the rest of the day. I made sure to identify that plant and know it well: Stinging Nettle.

I had no idea then that I would eventually welcome the presence of Stinging Nettle in our yard with fondness and respect, and be thankful that it’s here.

Nettle wakes us up, heightens our awareness and teaches us to pay attention.

Nettle affirms its own boundaries, and reminds us that we are tender and vulnerable.

Meet Stinging Nettle

The sting of Nettles is a common way that people awaken to its presence in the landscape. Its sting teaches us to pay attention and can motivate us to learn how to recognize it, but there are many other reasons to get to know Stinging Nettle. Humans throughout the world have had a long and rich relationship with it. This plant is a perennial member of the wild garden and it thrives in areas of anthropogenic disturbance, accompanying us wherever we settle.

Stinging Nettles grow in moist areas at the edges of forests and in places where trees have been cleared. They propagate through the spread of underground rhizomes, and by seeds that are carried on the wind or by creatures. You can find Nettle in farm yards and fields, in garden plots and pastures, and growing in urban and suburban yards and alleyways. They thrive along roadsides, fencerows, rail lines and the edges of abandoned industrial lots. If we have taken to calling Nettle a weed, we might actually wonder who the weed really is, us or the plant?

Some sources incorrectly identify Nettle as a non-native invasive plant, brought here to Turtle Island/North America by European colonizers. It is true that many unwanted, and even harmful, plants (and animals) hitched a ride or were intentionally brought to this continent by European settlers, like my ancestors, and every once in while the Eurasian genotype of Nettle (Urtica dioica) is found here. However, the bulk of it growing in North America is native to this place, in the sense that it has likely been here for as long as human beings have been here.

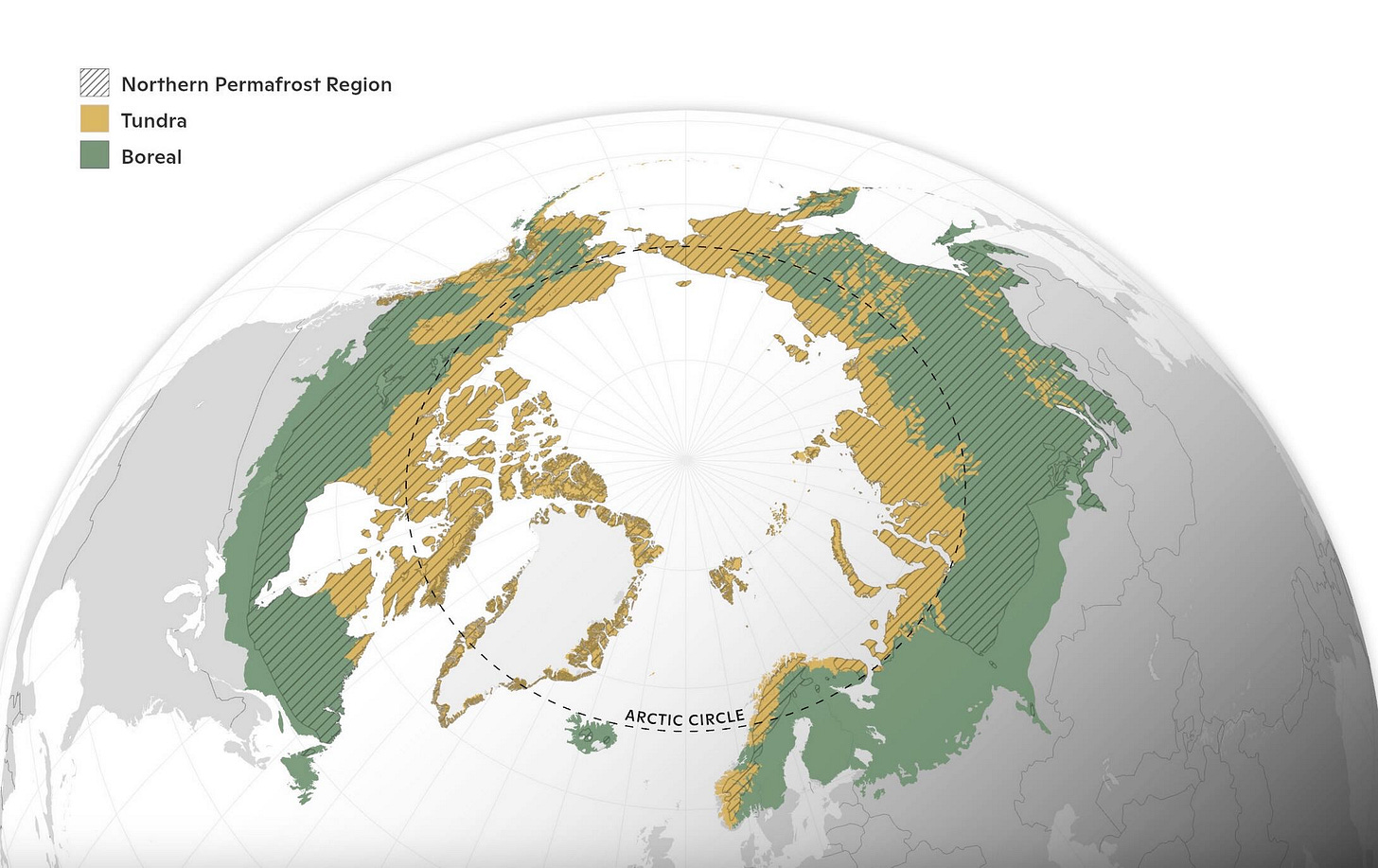

Nettle began as a circumboreal native, originating in Earth’s Boreal region and slowly moving southward over millennia, perhaps hitching a ride with humans who found their way up into the northern reaches and then continued to migrate from place to place, expanding southward.2

All Nettles in the Urtica genus tend to be tall with oppositely arranged lanceolate3 leaves. The species, Urtica dioica is native throughout Eurasia, but there are varieties of Nettle growing on every continent except Antarctica.

On North America, the native species of Stinging Nettle is known as Urtica gracilis, or Slender Nettle, and can be distinguished from the Eurasian species by subtle differences. The most noticeable of these is a more slender leaf—the Latin species name, gracilis, means “delicate or graceful”. Another significant difference is that U. gracilis is monoecious, with both male and female flowers on the same plant, while U. dioica, has separate male and female plant bodies.4

Here in Eastern North America, we have a second native variety, found in shady deciduous forests, called Wood Nettle (Laportea canadensis). Wood Nettle is a bit smaller than Stinging Nettle, has a leaf shape that is more ovate, and the leaves have an alternate growth pattern from the stem rather than the opposite pattern of the Urtica varieties. Its name is gentler on the tongue than Stinging Nettle, but Wood Nettle is also adorned with ferociously stinging hairs.

The stem and leaves of a Nettle plant are covered with tiny, hollow hair-like needles, called trichomes. When bare skin brushes against the sharp, bulb-like tips of the needles, they easily break and release a micro-blast cocktail of formic acid, acetylcholine, histamine and other compounds, that cause a painful stinging and burning sensation. For most people, this discomfort lasts a few hours and diminishes after washing with soap and water, but some develop more serious welts that require medical attention.

Perhaps the hot sting of Nettles offers us a kind of painful, but fairly safe reminder that we too are mortal and small. Like us, Nettle is a living being that is highly adaptable. In relationship with us, Nettle has the potential to heal, to nourish and to teach—if one is open to its wisdom. Nettle can cause us temporary discomfort, but if we take the time to know it, befriend it and learn its gifts, Nettle is a beneficial companion.

Nettle is steadfast, following us wherever we go.

Nettle shows us adaptability.

Nettle demonstrates thriving in locations of disturbance.

Nettle reminds us that we are vulnerable.

Nettle’s Bountiful Thread in the Weaving

Ecological Nettle

As humans clear land, Nettle is quick to move in as a pioneer species. Nettle shelters and preserves and enriches soil fertility when it otherwise might be barren after clearing. Their ability to draw nutrients up and accumulate them in their tissues makes them nutritious food for creatures like us who may consume them. When they die back those nutrients return to the soil, leaving it healthier than before they grew there.

Nettles bioaccumulate toxic substances like lead and PCBs. These toxins can be present in their tissues if the soil has been poisoned, which means we need to be careful where we harvest it for food. It is best to stay away from Nettle growing near rail lines, road ways or industrial sites. It also means that they can be used to help clean up toxic waste sites. In fact, tests have been done with promising results, which feels both hopeful and sadly dystopian to me. Nettles that used in this way would have to be disposed of in a designated hazardous waste site.5

Once Nettle moves in and stays for a little while, the plant supports many other kinds of lives. It is a necessary host plant for the Red Admiral (Vanessa atalanta), Small Tortoiseshell (Aglais urticae) and many other butterflies and moths. This means the adult butterflies and moths lay their eggs on the Nettle and the larva survive exclusively by eating its leaves until they transform into a winged adult.

Aphids love nettle as well and become juicy snacks for other insects like Lady bugs and parasitic wasps. The larva feeding on its leaves, and the seeds that Nettle produces are also important food for birds. Every passerine bird feeds it babies a variety of protein and fat-rich larva, so all native larval host plants, including Stinging Nettles are necessary to our dwindling bird populations, as well as for pollinators. Native larval host plants are an ecological backbone.

Nettle as Food

Stinging Nettles are flavorful wild greens that have been foraged and eaten by humans all over the world for millennia. If you don’t want to be stung while picking it, protect your hands and arms with gloves and long sleeves.

It is best for you and for the plants to limit yourself to harvesting in the spring and early summer, only clipping the top third or less of a plant that is 2’-3’ in height, but has not produced flowers yet. The top will regenerate and seeds will still form. If you clip it diagonally, this helps to keep rain water from rotting the stem.

Once the plant flowers and produces seeds, the leaves become tough and less palatable, and calcium crystals begin to form within it, which can impact the urinary system of people who eat it, particularly if they tend to have kidney stones. However, the seeds are edible and can be dried or flash roasted and sprinkled on things for added flavor, texture and nutrition.

Always leave several plants untouched, even though you know they can regrow and still flower and seed. Leaving them strengthens your capacity for forbearance, a practice of restraint and care. This is a human virtue that is sadly underrepresented in our world.

As a food, Nettles are most commonly used as a potherb, in soup or for tea. You can eat it raw with a little maneuvering, and if you would like to witness a lot people eating masses of raw Stinging Nettles, check out the annual World Nettle Eating Competition in Dorset, England!

There are numerous ways to gentle the sting of Nettles if shoving handfuls of raw nettle leaves into your mouth isn’t your thing. Hang it to dry, steam it or quickly blanch the leaves. To blanch, I drop the leaves, in batches, into a boiling pot of water, use a handled sieve to quickly lift them out and strain them, and then dump them out onto a clean kitchen towel or into a colander. I prefer blanching because it also provides a nutritious infusion for tea, or broth for soup, without diminishing the rich flavor and nutrition of the leaves.

Consider giving some of your cooled nettle broth back to the soil, a gesture of gratitude and reciprocity, returning nutrients to the land out of which they came . . .

Nettle‘s Cornucopia of Nutrients

Nutrient Cornucopia

Stinging Nettle is a deep green food source, that provides a blast of nutrition early in the growing season. As a biodynamic accumulator, Nettle draws up a large amount of nitrogen and many other nutrients from the soil, thereby concentrating them in its tissues. This is what makes it nutrient rich for animals, like us. Every part of the plant is edible. A metanalysis of the nutrients that this plant offers, establishes it as a “super food”, a banquet of essential compounds that support life.

It is rich in protein, holding every essential amino acid. Nettle is full of vitamins C, A, B complex E and K (a warning to those who might take blood thinners, but good news for most of us). It carries the minerals calcium, magnesium, manganese, iron and potassium. If you eat Nettle you will also be treated to an abundant array of bioactive phytonutrients, like chlorophyll, that are known to be important for cellular health and longevity.

When the plant dies back at the end of the growing season, it also replenishes the soil it grew from. Many organic gardeners use a fermented nettle extraction as a fertile tonic, applied to their gardens to increase the health, yield and nutritional content of their vegetables.6

Nettle as Medicinal Powerhouse

Nettles offer so many healing possibilities that some herbalists emphatically proclaim: When in doubt, give Nettles!

Recent science has validated much of what has been known and practiced by village healers all over the world for millennia about the use of Nettles for health and prevention of ailments. Nettle plants have compounds that stimulate the immune system, prevent cancer cells from proliferating, lower blood pressure, reduce inflammation, and promote cardiac health. They are high in anti-oxidants, and help reduce free radicals that increase as we encounter environmental stressors and that also occur during the normal aging process.7 They are high in anti-oxidants, and help reduce free radicals that increase as we encounter environmental stressors and that also occur during the normal aging process.

One of the most well documented medical benefits of Stinging Nettle is for urinary tract, kidney and prostate health. Research supports Nettle as an effective treatment to lessen symptoms for those who have BPH (benign prostate hyperplasia), a common and uncomfortable ailment that many people with prostate glands experience as they age.

Since ancient times, people in many cultures who suffer from the inflammatory pain of rheumatoid arthritis, particularly in the hands, have purposely exposed their joints to the sting of nettles. Contemporary research has supported claims for the benefits of this stinging practice, finding that compounds in the substance injected through its needle-like hairs actually inhibit the drivers of inflammation.

Nettle in Fiber Crafts

From ancient through contemporary times, humans have found Nettle to be an excellent dye for cloth. It has hardy fibers and has been twisted into useful cordage, spun into thread, and woven into fabrics at least since the Bronze Age. In addition to eating Nettles, the Anishinaabe People of the Great Lakes Area, and many other Indigenous peoples, have used Nettle fibers for cordage to make fishing nets.

In 1861, a piece of cloth was found, wrapped around some ancient cremated human remains that was dated back to the Bronze Age, 2800 years ago. It was assumed to be linen or flax, but was reanalyzed in 2012 with newer techniques of DNA analysis. The new data revealed that it was woven from Nettle fiber. Search for “Nettle cloth” on the internet, and you will find examples of beautiful contemporary cloth made of Nettle and colored with natural dyes.8

Nettle is steadfast, following us wherever we go.

Nettle is a nourisher, a strengthener and healer for us, other creatures and Earth.

Nettle reveals the wisdom that discomfort can make way for healing.

Nettle teaches us that we can dwell, side by side, with something potentially painful

and come to realize its gifts.

Being Humankind with Nettle

Being Humankind with Nettle

We have been in relationship with Nettle for thousands of years, eating it, wearing it, and being healed by it. Nettle awakens and humbles us with its sting. This plant supports our artistry, and teaches us about tenacity and reciprocity. Nettle is a beacon that reveals fertile soil and increases soil fertility.

What do Stinging Nettles receive from us? How do we reciprocate the gift?

The most obvious benefit Nettle receives from us is habitat, with very little thought or planning on our part. Over the ages, as we have made space for our own dwellings and enterprises, we’ve also made more habitat for Stinging Nettles. They thrive in edgelands and places of disturbance, which we’ve created in abundance and continue to make in large measure upon the Earth.

Highly adaptable Nettle plants are abundant, not scarce. And in their abundance, they’re cleaning up and restoring soils. They feed other creatures, which then feed other creatures . . . and Nettle can also feed us.

If we choose to collect and use Stinging Nettle (or any other plant or animal) to support or enhance our own wellbeing, we also have the responsibility to practice a few of the better ways of being human. Gather your Nettles where they grow naturally near to you. Cultivate gladness and gratitude for the blessing of their flavor and nutrients. When you harvest, imagine how you will return the blessing, and then do it, perhaps by pouring Nettle infusion back into the soil from which it grew.

Our human hearts contain the capacity for great tenderness. We have the ability to choose to act in ways that not only take care of ourselves, our loved ones and our local place, but in ways that include all that fit into the weaving Earthly life. When we are at our best as a species, we use our intelligence to support life rather than diminish it—both human and more than human lives.

Consciously participating in reciprocal relationship with Nettle, rather than engaging in a selfish taking, is a step into the beauty and belonging of being a part of a living cycle, rather than setting yourself apart from it. We can be Humankind, kin to all in a living world.

Nettle quietly asserts its sovereignty in our footprints.

Nettle is a mirror reflecting our human capacities, both flourishing and destructive.

Nettle offers the promise of healing relationship.

Befriend the sting of Nettle and learn from it.

And now for a little Stinging Nettle fun:

“Stinging Nettles” by Beans on Toast . . .

. . . So tell the dandelion it can tell the time

Pull your trousers up

Head to the river side

Blow the cobwebs off of your careless soul

Watch the sunrise when you're on your own

And I'll try to tell you to be careful

But you've never really lived

If you've never been stung by a stinging nettle

Thank you for reading this installment of Coming to Ground. If you liked what you read or heard here, please consider sharing it with others directly or by “restacking” this piece on Substack so that others might find it.

I truly feel that writing and reading are participatory arts, though each are quietly rendered in solitude. It is a gift to be able connect directly, however briefly, with others here on Substack. I would love to read and engage with your comments in response to this piece.

My work has no paywalls because I want these words to be free to all. Hitting the “Subscribe” button below will not cost you anything, paying is a choice.

If you can easily afford $5 per month or $50 for a year’s worth of my work, I will be deeply grateful for it. This is a labor of love that requires significant amounts of time, energy and attention.

Samuel Thayer, Nature’s Garden: A Guide to Identifying, Harvesting and Preparing Edible Wild Plants, Birchwood, WI: Forager’s Harvest, 2010, p10. www.foragersharvest.com

“. . . perhaps hitching a ride with humans. . .” This is me, imagining possibilities. I did not find research to back this particular idea up, but it seems very plausible with the breadth of evidence of human migration and the nearly global entwinement between Nettle and us.

lanceolate means shaped like a spear head, tapering to a point

“A recent study of Urtica dioica sensu lato (Henning et al., 2014) concluded that the American taxa, which are monoecious, form a clade that is clearly separate from the western Eurasian and African taxa, which are predominantly polygamous.” Note: I’d like to nerd this up a little and point out the ever-present undercurrent of colonization and anti-queerness that still rears its head and pervades science: Up until recently, U. gracilis was listed only as a subspecies of U. dioica: Urtica dioica ssp gracilis. However, it has been asserted by plant geneticists that U. gracilis is in fact a genetically different species from the Eurasian species. The species name “dioica” means that the male and female sexual parts are on different individuals of the plant--dioecious. Every U. gracilis plant is “monoecious”, it carries both male and female flower parts on each single plant. Even POWO affirming its species status. Despite this taxonomic designation, many botanists and naturalists continue to refer to U. gracilis as a subspecies of U. dioica. (POWO-”Plants of the World Online,”Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew is a highly regarded database of the world’s plants)

Dis – apart from + pose - place, position, separate. . . thrown away, separation from place

This conjures up disturbing thoughts and images of the enslavement of wild Nettle in organic factory farms. It could easily, and perhaps respectfully, be done in a home garden, but thoughts and images of the domestication of wild Nettle to serve the industry of organic factory farms to be a little horrifying. I would recommend eating it in small quantities and be glad of the blessing of its flavor and nutrients. Anything you don’t eat of the plant, like stems, can go right back out and into the soil.

“The root of the stinging nettle is used to treat mictional difficulties associated with benign prostatic hyperplasia, while the leaves are used to treat arthritis, rheumatism, and allergic rhinitis. Its leaves are abundant in fiber, minerals, vitamins, and antioxidant compounds like polyphenols and carotenoids, as well as antioxidant compounds like polyphenols and carotenoids. Stinging nettle has antiproliferative, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, analgesic, anti-infectious, hypotensive, and antiulcer characteristics, as well as the ability to prevent cardiovascular disease, in all parts of the plant (leaves, stems, roots, and seeds)” in: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9253158/

What a great article, I am a fellow nettle lover and rejoice in their resilience and all the benefits they bring with them. I have extracted fibre from nettles and run an informal workshop where we braided the fibres into bracelets, such a great activity. I've even got to tolerate and appreciate their stings! My only sadness is that my wife doesn't share my enthusiasm, I live in hope!